Warren Mason is a happy soul. You can tell by gazing into the warm pools of his deep brown eyes. Even before he breaks into a cheeky grin and wraps you in a bear hug, you know he’s one of the good guys.

He’s also a wandering soul. Whilst Tasmania has captured his heart and is now ‘home base’, Warren’s true home lies almost 2000kms away in north western New South Wales in a little town by the name of Goodooga. Dry, dusty and often stiflingly hot, Goodooga can reach temperatures in excess of 50 degrees Celsius in the summer months. Only the nearby Bokhara River provides relief. “Yeah, it’s crazy hot,” grins Warren. “That’s one of the things I love about Tassie…the cool weather.”

Warren grew up in between worlds. Listening to his deep soothing voice relay his experiences, it is difficult to imagine how one so balanced emerged from an abyss of disconnection. “My grandfather was the first Aboriginal to be living in the township of Goodooga,” he begins. “So there was always an expectation that our family followed the white ways. Basically I grew up as a proper little white boy with brown skin. We were bought up Catholic and we went to church every Sunday just like everyone else. I even went to pony club.”

Warren’s father was a shearer by trade before securing a job at the local council. “That was very important to him,” recalls Warren readily. “He valued the security that gave us. We were able to buy a house in town and dad earned his respect in the community. He became the local ambulance driver and invested a lot of himself in the township. Everyone loved him. He was a pioneer in terms of learning how to live in both worlds…both my parents were trailblazers in that sense.”

The other world Warren refers to was the indigenous camp ‘down by the river.’ “The camp was about one kilometre out of town – a tin camp in the most beautiful spot on the river’s edge. I was always told I couldn’t go there.” Warren pauses before he adds, “I was scared I’d get caught doing something wrong and disappoint mum and dad if I went, so as much as I wanted to, I never did. My uncle also drowned in the river, so as well as striving to fit in with the white fellas, I think my parents also avoided it for that reason. Looking back I was the real uptown nigger that didn’t have a sense of connection to my own people. I didn’t fit in either world.”

Warren traces a hand over his grandfather’s exemption certificate – a document issued in March of 1959 that outlines Charlie Mason’s chance to ‘be free of the Aboriginal Protection Act and live like a white man’. It was the start of change for the Mason family. The ability to ‘walk freely through town without being arrested’ and the means to ‘enter a shop or hotel’ are listed in black and white. Charlie also had special conditions imposed – he was not to speak in his native language or engage in dance, rituals or native customs. Likewise, associating with fellow indigenous people, including family, was strictly prohibited. The upshot of Charlie meeting these conditions is listed as being that he ‘may be eligible to live in town unsupervised.’

As a boy, and during a later period of return with his own young family in tow, Warren saw Goodooga fluctuate between a population of 300-500. “It’s always been about half and half in terms of the indigenous and white populations, and when I was young there was not very much integration. In the pub for example, there were separate black and white bars back then. That’s changed a fair bit now though.”

“There’s not a lot for young people in Goodooga and most of them tend to go to boarding school once they’re old enough,” explains Warren. “My first job was working the night shift at the Goodooga telephone exchange. It was real old style…I’d have to plug in the calls…I loved it because I just yarned to people all night. But I took off at 16 and headed to Brisbane chasing more opportunities.”

As a young man Warren turned his hand at a variety of callings. Uni to study a physical education degree, high level rugby league selection, running organic and permaculture properties, and in his own words, “Flying around farms on motorbikes chasing cows…that was probably the best fun of all.” His smile is nothing but contagious.

After meeting Tasmanian-born wife Donna, the pair returned to Goodooga to settle close to Warren’s family. “We bought the CWA rooms right in the middle of town and just opposite the pub,” says Warren. “It was a great spot. Kai and Josie could wander out and just go along to my parents place. It was a really good time and we were glad to be so close to them, especially when our own kids were so little.”

Warren also began to build an understanding of his heritage. “Funny enough, once us kids had left home, my parents rebuilt their connection to the camp. It’s ironic really…they spent all those years keeping us away and as soon as we left home they were back there themselves. Returning there now I feel a real connection. It probably took me a year to gain acceptance, but it felt good to be there. Interestingly, I feel it the most on the Murray River… where my grandfather is from. When I visit there, it really hits me that this is where I am from.”

“Going back helped me to deal with the sense of disconnect that I had always carried. It’s hard when you don’t understand where you came from or the culture you’re in now. I was just stuck in the middle of two worlds and needed to make sense of that.”

Just as things were coming together for Warren, tragedy struck the Mason clan. Warren’s younger brother passed away suddenly. “Kane was a real sportsman,” he describes. “He was a high level NRL player and was out with some mates one night enjoying himself. There was an altercation in the park and Kane was shot. It was unbelievable really.”

In Warren’s words, it was Donna who held the grief stricken family together. “My wife’s amazing,” he says evenly. “She held us altogether during that time when we were very lost. She’s always been there for the family and without her at that time I don’t know what would have happened. My parents really took it hard.”

Feeling the need to carve their own space, Warren and Donna made the decision to move their young family to Tasmania. “After what we went through, Donna in particular needed to get out of Goodooga. I could see the weight she was carrying and knew it was time for a fresh start. We all really needed it.”

The ‘Mason house of love’ was crafted by Warren and Donna on a quiet few acres half an hour from Hobart. Their casual, open vibe radiates a warm welcome and the house is often filled with friends who call in for a jam session. “I have a very strong connection to this place,” says Warren. “We built it from scratch and moved in just two weeks before our third child, Mahali, was born. It is definitely our home base and I can’t see us ever leaving.”

Music and art are both crafts that have come to Warren later in life. “Dad loved to draw and would often have pencils and paper scattered around, but I never got into art until later. When I did start to draw I sold my work at markets and I found that real sense of confidence and connection that came with selling a piece to be really rewarding. When someone sees value in your work, that is a real confidence boost for sure. It’s pretty cool when you express a part of yourself on paper and that actually resonates with someone else.”

As an adult, Warren has found meaning in a variety of artforms. Drawing, painting, sculpture, screen printing and, more recently, music. “Growing up music was definitely a presence around me. In shearing sheds, at the local bowls club and at school, but it wasn’t until later that I turned my own hand to it,” he explains. “Since Kane passed, I have found it’s a means to seek solace…a healing practice for sure.”

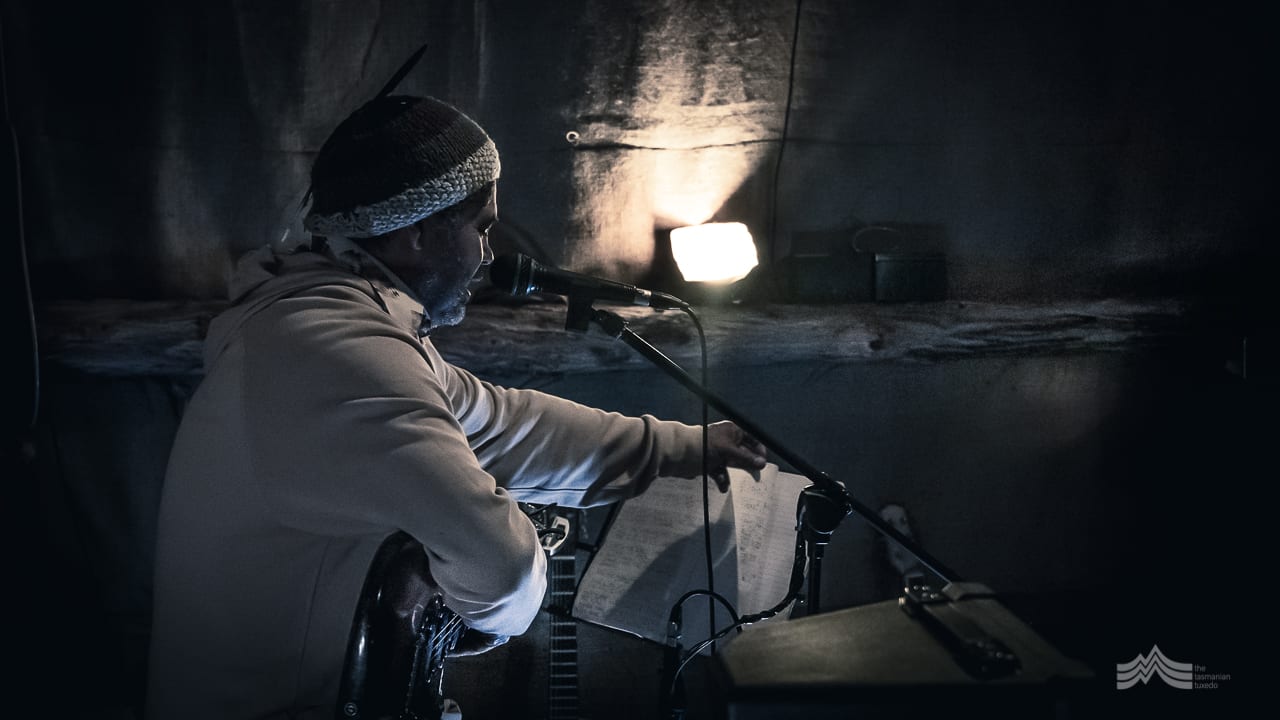

Warren’s music is the sound of who he is and where he’s from. Listening to his deep voice, one is easily lost in thoughts of how that journey has evolved. He’s a calm and accepting soul who’ll wrap you in rich melodies accompanied by warm acoustic guitar. It’s hauntingly beautiful, simple yet complex, serene yet powerful. It echoes with the voices of those who’ve come before him and the love that he wraps around his own family today.

From this healing has sprung renewed hope. The Tin Camp studio is Warren’s own creation – a healing space styled on a typical 1950s Aboriginal camp. It’s modelled not only on those found on the outskirts of Goodooga, but on the fringe of countless townships across Australia, both back then and still to this very day. It’s a safe, welcoming space for people of any background to gather, sit and share stories. “Initially the first Tin Camp I built here in Tassie helped me to share my own story about how the camp in Goodooga was central to the formation of my identity and all the questions that went along with it. That idea of never belonging in either place…the ‘uptown nigger’ to those in the camp and just a ‘nigger’ to those living in the town. But it’s become more than that now.”

“The Tin Camp is a place that’s open to everyone’s stories.”

Constructed from local salvaged materials, just as a true tin camp would be, Warren can put the Tin Camp together in a couple of days. It’s a warm and welcoming space, raw and gritty, echoing his memories back home. No aircon, hessian on the walls, and no floors. “Aside from a workshop and performance space, it also includes a recording studio. It’s a place for music and story to go on the record for the next generation to appreciate, enjoy and learn from,” says Warren. Stories may take the form of art, music, spoken word, comedy or soap box. “It’s a place of healing both for those who choose to share, and those who chose to listen…and I’ve found that it’s really powerful.”

Kicking off at the Nayri Niara festival on Tasmania’s Bruny Island in early 2019, The Tin Camp is going from strength to strength. In his newfound role as curator, Warren is gently finding his feet with a project that can help others. “Really what I’m about is taking this relocatable space to others, to help their journey and to get people talking. The Tin Camp Studio offers a music, art and workshop space to bring people together. We’re about recording stories…and having those documented is really important for the future. We can all appreciate, learn from, and enjoy other people’s stories.”

Taking the Tin Camp Studio on the road is Warren’s next big adventure. “This is something that really means a lot to me and has helped my healing for sure,” he says. “It’s awesome to see how other people react to it and what the space can play home to. It’s always a good night in the camp.”

Find out more about Tin Camp Studios via the website and Facebook page

Check out Warren performing his song ‘Birthday’ on the Tin Camp Studios Youtube channel